It is approaching that time again. My life is characterised by two years of calm followed by a year of building tension thinking "what the hell am I going to do next?". My contract at Liverpool finishes in March and I'm starting to look for jobs.

My first plan was to apply for NERC and Royal Society fellowships. The advantage of these schemes is that they allow you the autonomy to research what you want (in line with original proposal, otherwise the funding bodies might get grumpy) and once you have fellowship status you can apply for grants as principle investigator. Also, universities are strongly encouraged to make research fellows permanent members of staff after the end of the funding, though this is by no means guaranteed. The downside is that they are very competitive, the NERC fellowship covering all the natural environment disciplines, from counting birds and geology to molecular biology and the RS fellowship open to all scientific disciplines. Applications therefore have to be exquisitely constructed things of intricate and arse-covering beauty.

I had an idea for a proposal, I think it was a good one, and I had people who wanted to collaborate and also thought that it would work or at least be interesting. However, I then sat and thought about my publication record.

As a postdoc, papers are everything. They are the only currency that employers and funders understand, they define your career and symbolise your scientific ability. Whether this should be the case, or they are a fair representation is moot. You have to have publications to prove that you are worth employing and that is that. Speaking to an academic who had been on one of the NERC fellowship review panels he reckoned that he'd hope to see three, first-author papers published in a good quality microbial ecology journal for a NERC fellowship applicant in microbial ecology. 'Good quality journal' gets us into the realm of impact factors. Journals are basically judged by the number of times that the papers in them are cited in other papers. It's like climbing up Google's hit list, but harder and with less reward.

The other critical point is 'first-author paper'. There are two positions you want to be in the list of authors on a biology paper (I'm not sure that this necessarily holds for other disciplines), first, or last. First broadly means that you wrote it and contributed significantly to the scientific content. Last means that you concocted the proposal, got the funding, supervised the work and probably edited the paper. Those positions in between have a sort of sliding scale of worth with slap-bang in the middle being the bottom of the pecking order. Experiments are never as straight-forward as 'Bob did the work and Alice' got it funded so there can be jockeying for position and everything gets political, particularly if more than one group was involved in the research.

Which brings me to my own publication record. Brace yourselves, this is not pretty; it is a Frankensteinian creation of little consistency. I start at the very beginning (I'm told it's a very good place to start):

1. Isolation of viruses responsible for the demise of an Emiliania huxleyi bloom in the English Channel.

Wilson, W. H., Tarran, G. A., Schroeder, D., Cox, M., Oke, J., and Malin, G.

Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the UK, 2002.

PDF

2. Aminobacter ciceronei sp. nov. and Aminobacter lissarensis sp. nov., isolated from various terrestrial environments.

McDonald, I. R., Kampfer, P., Topp, E., Warner, K. L., Cox, M. J., Connell Hancock, T. L., Miller, L. G., Larkin, M. J., Ducrocq, V., Coulter, C., Harper, D. B., Murrell, J. C., and Oremland, R. S.

International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 55; pp 1827-1832; 2005. Abstract.

3. Use of DNA-stable isotope probing and functional gene probes to investigate the diversity of methyl chloride-utilizing bacteria in soil.

Borodina, E., Cox, M. J., McDonald, I. R. & Murrell, J. C.

Environmental Microbiology vol 7; pp 1318-1328; 2005

Abstract.

4. Stable-isotope probing implicates Methylophaga spp. and novel Gammaproteobacteria in marine methanol and methylamine metabolism.

Neufeld, J. D., Schafer, H., Cox, M. J., Boden, R., McDonald, I. R., and Murrell, J. C.

The ISME Journal vol 1; pp 480-491; 2007

Abstract.

5. A multi-loci characterization scheme for Shiga-1 toxin encoding bacteriophages.

Smith, D. L., Wareing, B. M., Fogg, P. C. M., Riley, L. M., Spencer, M., Cox, M. J., Saunders, J. R., McCarthy, A. J., and Allison, H. E.

Applied and Environmental Microbiology pp (accepted 08/10/2007)

Abstract.

Those are the ones that are out at the moment, there is one more that is currently going through the submission process that I won't jinx by listing and three more that are in various stages of writing that should, hopefully, all be published at some point.

Now, what's the first thing you notice about those four beauties? Firstly, where are the first and last authorships? In a couple of those papers I do an excellent job of squatting in the perfect centre, the nadir of the author list. I should have at least one first author paper from my PhD, and this is currently in production, but the delay in writing (purely my own fault) has meant that I have a gap between 2005 and 2007. Not good.

Secondly, what's the theme here? Is it immediately apparent that I am a focussed researcher with a consistent and driven career plan in molecular marine microbial ecology? Is it buggery. I start with marine algal viruses (the work I contributed to this paper was actually done as an undergraduate during a summer project in 1999), move on to a couple of soil bacteria, have a mooch about in stable-isotope probing (one soil, one marine, both with work from my PhD) and then leap gleefully into shiga-toxigenic phage (these are the ones that make E.coli 0157 nasty).

Looking at the positive, they are all in quite good journals. Delving into the innards of the Journal Citation Reports and coming out smelling of dust and politics, it is possible to discover that Environmental Microbiology is doing the best with an impact factor of 4.630, Applied and Environmental Microbiology is at 3.532, IJSEM is at 2.662 and Journal of the MBA UK brings up the rear with a factor of 0.778 (though please don't judge it harshly, it's a cute little journal from one of the oldest marine biology societies in the world - I say one of as I think it might be the oldest, but can't find the proof). The ISME Journal was only out this year and you need three years of article count data before an impact factor can be calculated.

So, considering the above and the fact that the deadline for fellowship submissions is 1st November I decided to wait a year before submitting an application. With no first-author papers, no chance. Which leaves me taking remedial action to boost what publications I've got in order to be able to make convincing applications for a second postdoctoral position. First job, that knotty paper from my PhD thesis that has been dogging me (and I have been dogged about) for some time.

Tuesday 23 October 2007

Excuse me Sir? May I see your papers?

Posted by

Mike

at

14:00

![]()

Labels: fellowships, impact factors, jobs, journals, NERC, Papers, postdocs, publications, Royal Society

Tuesday 9 October 2007

Can't make up my mind about Venter

Craig Venter causes me problems. Do I like what he does or not? He is a controversial figure; controversy that I think mainly stems from his intention to patent the human genome sequence produced by his company Celera. In a couple of weeks, on Oct 25th, he is releasing his autobiography A Life Decoded: My Genome: My Life (suffering from the sort of dreadful title long associated with scientists autobiographies see here) of which two extracts have been published in the Guardian (extract 1, extract 2), the first about the race between the two human genome projects and the second about his time in Vietnam. Coincidentally, this is also the predicted date for his creation of synthetic life. How's that for advertising?

Working in microbial ecology I had heard of Venter and the race to produce the first human genome sequence - incidentally, neither the Celera or Human Genome Consortium versions are actually complete, the assemblies of the separate bits of sequence change relatively regularly and there are repetitive tracts that may be impossible to correctly sequence and assemble (we're currently up to version 36.2 according to the NCBI) - but my research was in an entirely different area of biology. Then came Sorcerer II and attempt to sequence the sea, or at least all the bacteria in it that pass through a 0.8 micron filter, but not a 0.1 micron one. The papers containing the detail of the expedition and some of the initial findings were published in the journal PLoS Biology. This produced a vast dataset of marine bacterial DNA sequence, massively increasing the amount of DNA from these organisms available in the DNA databases. Indeed they had to set up their own database to manage the data (and wouldn't have been very popular had they not).

This is where I start to have problems. The data is an excellent resource for people to see whether their favourite gene is present in the samples, but isn't the work bad science? There is no hypothesis being tested by sequencing in this way other than "we can sequence marine bacteria" (which reminds me of my favourite scientific paper - An Account of a Very Odd Monstrous Calf, by Robert Boyle pdf). On the other hand if you have the money and resources to do this kind of thing, why shouldn't you? It is an expedition rather than an experiment. See? Can't make up my mind. There is a presentation from Venter (on his yacht in a typically tropical part of the trip) available here, please ignore the Roche advert and note that even famous scientists can get a bad case of the "this next slide shows".

I think my problems boil down to motivation. Why does Venter want to sequence and patent the human genome? Why was one of the genomes of his own? And more recently why did the project after that have the aim of creating synthetic life? Is it massive hubris or is that entirely unfair?

Still - his competition to be the first to sequence the human genome certainly accelerated both projects and I find the global ocean sequencing data quite handy, plus he is talking about application of a synthetic bacterium, of which his Mycoplasma laboratorium is likely to be the first (as I understand it, currently there is a synthetic genome that has yet to be stuck in a cell and only then does it become an organism), in removal of atmospheric CO2 (echoes of Lovelock's call for direct action there).

I'm still undecided, but in case you want to see more of him, below is a TED talk covering some of his efforts. It was given in 2005 and predicted and synthetic bacterium in 2007 followed by a synthetic eukaryote by 2015. One down, one to go.

Incidentally, the TED talks site is a great place to find fascinating talks - my favourite that I've listened to so far being Sir Ken Robinson - his description of academics on the dance-floor is entirely accurate (although I'd add more pogoing).

Posted by

Mike

at

14:24

![]()

Labels: bacteria, climate change, Craig Venter, DNA sequencing, genome, Lovelock, microbiology, ocean, TED talks

Thursday 27 September 2007

Pipe dreams?

I noticed in my Nature alert today a short letter from James Lovelock and Chris Rapley about a potential mechanism for secreting atmospheric CO2 in the seas. The plan described is to have large pipes (and they mean large - 100-200 m in length and 10 m in diameter!) floating in the sea vertically, allowing mixing of seawater above and below the thermocline. Phytoplankton (algae) require three main things in order to grow, light, nutrients and CO2. The thermocline is a divide between the sun warmed surface water, which has sufficient light and CO2 for growth, but few nutrients, and the cool, deeper water which is obviously too dark, but full of nutrients that have fallen out of the surface layers. There are natural places where the two waters mix called upwellings - here you get blooms of phytoplankton which use up CO2 as they photosynthesise. The pipes would simulate these upwellings and stimulate the uptake of CO2 by the phytoplankton. Phytoplankton also produce dimethyl sulphide (DMS - the characteristic "smell of the sea") which can stimulate the formation of clouds - cooling the planet by preventing the suns rays reaching the surface. The story has also been picked up by the BBC here (and the New Scientist and umpteen other places - Nature is quite good at getting its stories published elsewhere before they have themselves! My girlfriend used to tell me all the latest research news from the fee paper Metro before I'd even received the original articles) and has some nice diagrams of the pipes in action.

Atmocean, a US company have been developing such a system themselves and have a suitably dramatic video on youtube (note the use of Clubbed to Death by Rob D, as heard on the soundtrack of The Matrix - it signifies 'bad stuff happening').

It is great that someone is proposing some direct action with some science behind it. The idea is an interesting one, but probably won't work. Bold statement huh? I'll try and justify it.

There are fairly large practical difficulties such as the fact that the Atmocean CEO Phil Kithil in an interview as part of the BBC article says that "134 million pipes could potentially sequester about one-third of the carbon dioxide produced by human activities each year" - it's not clear whether this refers to current levels or not as by the time pipes were in place you'd need a lot more as we'll have chucked a whole lot more into the atmosphere, but anyway, installing that many pipes would be quite a task.

Creating phytoplankton blooms doesn't only increase the level of DMS in the atmosphere above the bloom, it also increases the levels of other gases, including methyl bromide and isoprene (see this paper) . Methyl bromide is a major source of bromide to the upper atmosphere and bromide is better at destroying ozone than the chlorine from CFCs, so this would have the potential to enhance ozone layer destruction. Isoprene has a complex, and not completely understood role in atmospheric chemistry - increasing the levels of these compounds in the atmosphere is likely to have an effect, which may be beneficial or otherwise, but as the roles of these compounds in the atmosphere are less well understood than DMS is stimulating their production wise?

There is also likely to be a massive impact on the biology of the sea; organisms have complex and subtle interrelationships that we are barely starting to understand, particularly at the microbiological level - how this will effect the climate is also unknown.

Charles Rapley points out in the BBC article that his and Lovelock's letter is designed to stimulate discussion about direct action, which I hope it will - international agreements like Kyoto being mired in political torpor, but there is a danger that such dramatic suggestions, that to non-scientists could sound like science fiction madness, only add weight to climate change apathy. It is the style of the solutions that captures the imagination rather than the problem itself (think giant solar reflectors in space and dumping iron filings in the sea).

However, if anyone can truly stimulate action it is Lovelock - his invention of the electron capture detector a sensitive device for measuring tiny amounts of chemicals in the atmosphere, prompted Rachel Carson's novel The Silent Spring, ultimately leading to the genesis of the entire green movement. For further reading James Lovelock's website is here.

Posted by

Mike

at

20:22

![]()

Labels: carbon dioxide, climate change, DMS, isoprene, Lovelock, methyl bromide, Nature, upwellings

Friday 14 September 2007

SGM Edinburgh Talk

SGM 6/9/07

From: mikeyj, 1 week ago

Presentation given at SGM Metagenomics Hot-topic Session in Edinburgh, UK

Link: SlideShare Link

Posted by

Mike

at

17:55

![]()

SGM Presentation

A quick note about the Slidecast I promised. I have the sound track, but recorded it at too high a quality in Audacity, (which is great, in case you haven't tried it) so I need to squeeze it down in size a bit - suggestions welcomed. In the meantime, you can whet your appetite on the slides themselves.

Posted by

Mike

at

17:49

![]()

Labels: presentations, SGM, Slideshare, talk

Secrets of Shipwrecks

My last summer student of the season just finished. For the past eight weeks I've been supervising James Wong and Steve Hooton as they attempted to wrestle with projects entitled "Bacterial Treasure! Secrets of Shipwrecks"...an excellent example of naff titling. They were both looking at different aspects of bacterial diversity in some quite tricky samples - lumps of wood rescued from the wreck of the James Eagen Layne, a Liberty Ship torpedoed on 21st March 1945 on her maiden voyage and currently sat 24 m down in Whitsand Bay. She was carrying US army military cargo, which included tanks parts and pick axes, and a deck cargo of motorboats and timber; it is samples of the timber that we managed to get our hands on.

My dad is an advanced diving instructor and he and some of the other instructors at Fort Bovisand were kind enough to dive down to the JEL and extract some samples of timber. Not as easy a process as it sounds when I demanded as little handling as possible of the samples by the divers to maintain the natural bacterial population of the samples. They added tags to the zip-lok bags that I provided them with and also a method of cleaning the knife used so that, although it wasn't sterile, it wasn't contaminating the samples with grease used to protect the blades of divers' knives - as you can see below:

And this is a piece of wood that was actually sampled (the end was trimmed off one of those loose spars):

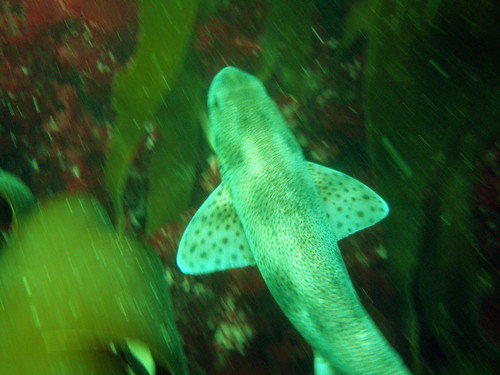

And just to prove that there's big stuff down there for those who like their organisms larger: gratuitous dogfish, spider crab and sea-snail shots (all photos taken by my dad!):

Another tricky part of the exercise was actually getting the samples from Plymouth to Liverpool as they needed to be stored in dry ice - with a little help from some friends at the Diving Disease Research Centre and Plymouth Marine Laboratory we were able to purloin some dry ice and get the samples couriered up. Then the fun began!

James was sponsored by the Society for General Microbiology and concentrated on attempting metaproteomics on the samples, looking for cellulases and chitinases. He used protein gels to look at some strains of bacteria that had been isolated from the same area. Steve concentrated on extracting DNA from the wood samples and using DGGE (denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis) to characterise the populations of bacteria in the different samples and was sponsored by the Nuffield Foundation. Both projects were a tall order and both students rose to the challenge. Our major problem was the nature of the samples themselves, the wood wasn't very degraded and there was evidence that it had been treated in some way (a strong smell of bitumen when some of the samples were freeze-dried was a give-away!). There wasn't likely to be much DNA or protein present in the samples, and the presence of co-extracting compounds was likely to foil down-stream analyses. In the end, after many attempts of different methods and James' and Steve's tenacity, it became clear that we weren't going to be able to extract any DNA or protein from the samples. A bit of a shame, but not really the ultimate aim of the projects.

These summer studentships are a great opportunity for undergraduates between their second and final years, to get experience of a working lab and of carrying out a defined piece of research, with all the frustrations that go with that intact. I was lucky enough to do one myself as an undergrad, at the Marine Biological Association with Willie Wilson and it really gives you a taste for research. Plus as the students are new to the subject and the methods and full of enthusiasm, it's good to view things through their eyes when it's easy to become jaded.

We never managed to find any bacterial treasure (or even a scrap of DNA or protein) but hopefully they both enjoyed themselves and they'll certainly get a head-start in their final year research projects. Both my students from last year are now doing PhDs or applying for them and knowing that a summer project may have helped them decide to go ahead with that (or at least not put them off it) is a really satisfying feeling. Hopefully James and Steve enjoyed themselves too!

Posted by

Mike

at

15:03

![]()

Labels: bacteria, diving, Nuffield, SGM, shipwrecks, Summer students

Monday 10 September 2007

To coin a phrase.

MetaprotogenomoSIPolomics is where it's at. At least that's what I tried to convince the audience at the Edinburgh SGM meeting with my slightly rushed and results-lite presentation. I failed to record the talk, but will do a soundtrack myself so you can get an 'almost there' feel. Hopefully a Slideshare slidecast is all it's cracked up to be! When I get some time I'll mention some of the more interesting talks too, it was a good meeting, my buttocks have just recovered from sitting through it.

Posted by

Mike

at

14:56

![]()

Saturday 1 September 2007

A quick note

Just getting packed for Edinburgh. The talk is at least set in my mind, the slides will change several times - it's not until Thursday and I keep thinking that I'll have all the evenings free. There are too many people to catch up with for that to be true!

Last week (or the one before) I stuck a note on my Facebook profile asking for help and suggestions writing the talk (mainly help avoiding bullet points - ick) and received 13 stunningly rude and innuendo laden replies. It's not me, it's my friends. It did serve as a reminder that there is, somewhat inevitably, a Facebook group for microbial ecologists, Microbial Ecologists United - linky (hope that works). Not as active as it could be, I always have intentions of posting job ads at least, lets see if I manage.

May update during the week if I find a nice wifi hotspot - otherwise, wish me luck!

Wednesday 29 August 2007

All talk...

The Society for General Microbiology is a UK charity that offers funding for microbiologists and also holds a biannual meeting. As it's a general microbiology society and not specific to microbial ecology my interest in meetings tends to vary from year to year. Next week in Edinburgh is the 161st meeting and it looks like an interesting one. I'm not saying that simply because I'm presenting. Honest.

I'm in the Hot-Topic session called “Post-genomic analysis of microbial function in the environment” which is joint with the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) who sponsor my current project. I was a little bit surprised to get a talk, when I submit an abstract for a poster I always tick the 'would you like to be considered for an oral presentation?' box as posters are more easily ignored, and this will probably be the largest audience I've spoken to (at least since assembly at school, we had a big year). As I'm an offered paper rather than an invited speaker I get a slightly shorter slot of 15 minutes. Three to five minutes of that will be reserved for questions leaving me to prepare a 10-12 minute talk. It's an odd length of time, I really can't introduce the subject and cover all the aspects that I would ordinarily include in a longer talk. I think I'm going to give a broad taster of what I'm doing, focussing on approaches that we've decided to take and why rather than presenting detailed results on any one of them. It is easy to slip onto the habit of chucking together formulaic presentations and the shorter time has really made me think about this one.

Hopefully you'll be able to judge for yourself if you can't make it to the meeting (or nod off during my bit – I'm in a fidgety session, just before lunch on the final day of the meeting) as I'll upload the slides to Slideshare and link here. I've also got hold of a lapel microphone and will be recording my talk on my MP3 player. I should be able to sync the two together; voila! a fascinating talk on the metagenomics and metaproteomics of marine polysaccharide-degrading bacteria without the added distraction of my handsome physog. Hopefully it'll also allow me to find out what's wrong with my talks, they always seem to pass in a blur and and people are (mostly) polite afterwards – good for the ego, not so good for improving your technique.

On the topic of talks I should also plug my boss' talk, Prof. Alan McCarthy will be enlightening a rapt (and probably chuckling) audience with the ecology of shiga-toxigenic phage (the ones that make Escherichia coli 0157 as nasty as they are). He's not written it yet - allowing me to be a little smug - as he's being overwhelmed with everyone else's posters to check over; but he is always amusing. No pressure Alan.

Posted by

Mike

at

13:40

![]()

Labels: Meetings, NERC, presentations, SGM

Tuesday 21 August 2007

In Our Time

I've sporadically kept a blog before about an Alternative reality game (Perplex City - now on sabbatical) and found that I really wanted to post about so many more things than purely that. One of the main distractions was microbial ecology and this blog is my attempt to give free rein to that distraction. Though in this first post I still can't quite escape. Through the blog of one of the creators of Perplex City, Adrian Hon I came across a series of programmes on Radio 4 called In Our Time, hosted by Melvyn Bragg (gratuitous photo of famous bouffant do left).

Though in this first post I still can't quite escape. Through the blog of one of the creators of Perplex City, Adrian Hon I came across a series of programmes on Radio 4 called In Our Time, hosted by Melvyn Bragg (gratuitous photo of famous bouffant do left).

I don't listen to the radio very much, it's something I associate with being driven to swimming lessons as a child (not that I didn't like swimming) and The Archers omnibus on a Sunday when my mum was doing the ironing (idyllic huh? And who'd have thought that Debbie Aldridge was much better as a comedian?), but these sounded great; panel discussions on all manner of subjects including hell, negative numbers, Jung and the Higgs Boson (I have a prejudiced view of the Higgs Boson that for the moment I will refrain from letting forth).

Being quite cautious when it comes to sampling new things I scrolled down the substantial list of programmes in the archive, all still available to listen to, to find one that I might know something about already (goodbye chaos theory and Wittgenstein) and found Microbiology. I fully expected to get annoyed at inaccuracies, or at the ecological aspects of microbiology being ignored in favour of the grisly, crowd-pleasing medical aspects, but was unable to. It was a lovely potted history of the subject which managed to cover the history of its development, its impact and future potential in only forty minutes, less than your average undergraduate lecture. Culturabilty, phylogenetics and similar were all mentioned

Though some of the anecdotes anyone with a GCSE in science will have come across - Edward Jenner injecting poor James Phipps with pus and coming up with vaccination for example - other parts of the programme were more novel. I'm sure I've always been taught about microbiology's origins via the history of microscopy and that the two were inextricably linked, but one of the panellists, Andrew Mendelsohn pointed to the real beginnings of the subject being in studies of function of microorgansisms - physiology rather than microscopic observation. It's nice to make these little connections that I've failed to fully appreciate and happily function has also been the subject of my own work. Definitely worth a listen.

And in case you get hooked on In Our Time (sorry), Adrian also has a discussion site about the programme, After Our Time.

Posted by

Mike

at

16:28

![]()

Labels: Adrian Hon, in our time, microbiology, radio