I noticed in my Nature alert today a short letter from James Lovelock and Chris Rapley about a potential mechanism for secreting atmospheric CO2 in the seas. The plan described is to have large pipes (and they mean large - 100-200 m in length and 10 m in diameter!) floating in the sea vertically, allowing mixing of seawater above and below the thermocline. Phytoplankton (algae) require three main things in order to grow, light, nutrients and CO2. The thermocline is a divide between the sun warmed surface water, which has sufficient light and CO2 for growth, but few nutrients, and the cool, deeper water which is obviously too dark, but full of nutrients that have fallen out of the surface layers. There are natural places where the two waters mix called upwellings - here you get blooms of phytoplankton which use up CO2 as they photosynthesise. The pipes would simulate these upwellings and stimulate the uptake of CO2 by the phytoplankton. Phytoplankton also produce dimethyl sulphide (DMS - the characteristic "smell of the sea") which can stimulate the formation of clouds - cooling the planet by preventing the suns rays reaching the surface. The story has also been picked up by the BBC here (and the New Scientist and umpteen other places - Nature is quite good at getting its stories published elsewhere before they have themselves! My girlfriend used to tell me all the latest research news from the fee paper Metro before I'd even received the original articles) and has some nice diagrams of the pipes in action.

Atmocean, a US company have been developing such a system themselves and have a suitably dramatic video on youtube (note the use of Clubbed to Death by Rob D, as heard on the soundtrack of The Matrix - it signifies 'bad stuff happening').

It is great that someone is proposing some direct action with some science behind it. The idea is an interesting one, but probably won't work. Bold statement huh? I'll try and justify it.

There are fairly large practical difficulties such as the fact that the Atmocean CEO Phil Kithil in an interview as part of the BBC article says that "134 million pipes could potentially sequester about one-third of the carbon dioxide produced by human activities each year" - it's not clear whether this refers to current levels or not as by the time pipes were in place you'd need a lot more as we'll have chucked a whole lot more into the atmosphere, but anyway, installing that many pipes would be quite a task.

Creating phytoplankton blooms doesn't only increase the level of DMS in the atmosphere above the bloom, it also increases the levels of other gases, including methyl bromide and isoprene (see this paper) . Methyl bromide is a major source of bromide to the upper atmosphere and bromide is better at destroying ozone than the chlorine from CFCs, so this would have the potential to enhance ozone layer destruction. Isoprene has a complex, and not completely understood role in atmospheric chemistry - increasing the levels of these compounds in the atmosphere is likely to have an effect, which may be beneficial or otherwise, but as the roles of these compounds in the atmosphere are less well understood than DMS is stimulating their production wise?

There is also likely to be a massive impact on the biology of the sea; organisms have complex and subtle interrelationships that we are barely starting to understand, particularly at the microbiological level - how this will effect the climate is also unknown.

Charles Rapley points out in the BBC article that his and Lovelock's letter is designed to stimulate discussion about direct action, which I hope it will - international agreements like Kyoto being mired in political torpor, but there is a danger that such dramatic suggestions, that to non-scientists could sound like science fiction madness, only add weight to climate change apathy. It is the style of the solutions that captures the imagination rather than the problem itself (think giant solar reflectors in space and dumping iron filings in the sea).

However, if anyone can truly stimulate action it is Lovelock - his invention of the electron capture detector a sensitive device for measuring tiny amounts of chemicals in the atmosphere, prompted Rachel Carson's novel The Silent Spring, ultimately leading to the genesis of the entire green movement. For further reading James Lovelock's website is here.

Thursday, 27 September 2007

Pipe dreams?

Posted by

Mike

at

20:22

![]()

Labels: carbon dioxide, climate change, DMS, isoprene, Lovelock, methyl bromide, Nature, upwellings

Friday, 14 September 2007

SGM Edinburgh Talk

SGM 6/9/07

From: mikeyj, 1 week ago

Presentation given at SGM Metagenomics Hot-topic Session in Edinburgh, UK

Link: SlideShare Link

Posted by

Mike

at

17:55

![]()

SGM Presentation

A quick note about the Slidecast I promised. I have the sound track, but recorded it at too high a quality in Audacity, (which is great, in case you haven't tried it) so I need to squeeze it down in size a bit - suggestions welcomed. In the meantime, you can whet your appetite on the slides themselves.

Posted by

Mike

at

17:49

![]()

Labels: presentations, SGM, Slideshare, talk

Secrets of Shipwrecks

My last summer student of the season just finished. For the past eight weeks I've been supervising James Wong and Steve Hooton as they attempted to wrestle with projects entitled "Bacterial Treasure! Secrets of Shipwrecks"...an excellent example of naff titling. They were both looking at different aspects of bacterial diversity in some quite tricky samples - lumps of wood rescued from the wreck of the James Eagen Layne, a Liberty Ship torpedoed on 21st March 1945 on her maiden voyage and currently sat 24 m down in Whitsand Bay. She was carrying US army military cargo, which included tanks parts and pick axes, and a deck cargo of motorboats and timber; it is samples of the timber that we managed to get our hands on.

My dad is an advanced diving instructor and he and some of the other instructors at Fort Bovisand were kind enough to dive down to the JEL and extract some samples of timber. Not as easy a process as it sounds when I demanded as little handling as possible of the samples by the divers to maintain the natural bacterial population of the samples. They added tags to the zip-lok bags that I provided them with and also a method of cleaning the knife used so that, although it wasn't sterile, it wasn't contaminating the samples with grease used to protect the blades of divers' knives - as you can see below:

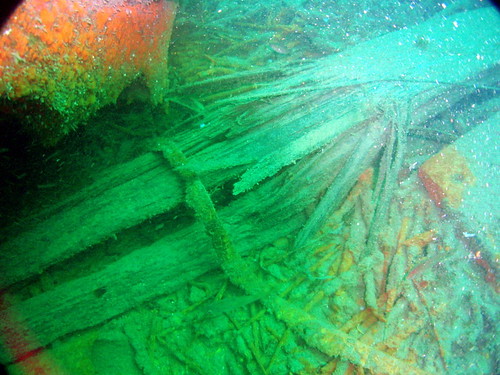

And this is a piece of wood that was actually sampled (the end was trimmed off one of those loose spars):

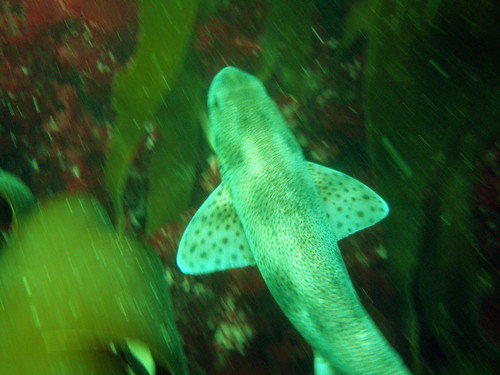

And just to prove that there's big stuff down there for those who like their organisms larger: gratuitous dogfish, spider crab and sea-snail shots (all photos taken by my dad!):

Another tricky part of the exercise was actually getting the samples from Plymouth to Liverpool as they needed to be stored in dry ice - with a little help from some friends at the Diving Disease Research Centre and Plymouth Marine Laboratory we were able to purloin some dry ice and get the samples couriered up. Then the fun began!

James was sponsored by the Society for General Microbiology and concentrated on attempting metaproteomics on the samples, looking for cellulases and chitinases. He used protein gels to look at some strains of bacteria that had been isolated from the same area. Steve concentrated on extracting DNA from the wood samples and using DGGE (denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis) to characterise the populations of bacteria in the different samples and was sponsored by the Nuffield Foundation. Both projects were a tall order and both students rose to the challenge. Our major problem was the nature of the samples themselves, the wood wasn't very degraded and there was evidence that it had been treated in some way (a strong smell of bitumen when some of the samples were freeze-dried was a give-away!). There wasn't likely to be much DNA or protein present in the samples, and the presence of co-extracting compounds was likely to foil down-stream analyses. In the end, after many attempts of different methods and James' and Steve's tenacity, it became clear that we weren't going to be able to extract any DNA or protein from the samples. A bit of a shame, but not really the ultimate aim of the projects.

These summer studentships are a great opportunity for undergraduates between their second and final years, to get experience of a working lab and of carrying out a defined piece of research, with all the frustrations that go with that intact. I was lucky enough to do one myself as an undergrad, at the Marine Biological Association with Willie Wilson and it really gives you a taste for research. Plus as the students are new to the subject and the methods and full of enthusiasm, it's good to view things through their eyes when it's easy to become jaded.

We never managed to find any bacterial treasure (or even a scrap of DNA or protein) but hopefully they both enjoyed themselves and they'll certainly get a head-start in their final year research projects. Both my students from last year are now doing PhDs or applying for them and knowing that a summer project may have helped them decide to go ahead with that (or at least not put them off it) is a really satisfying feeling. Hopefully James and Steve enjoyed themselves too!

Posted by

Mike

at

15:03

![]()

Labels: bacteria, diving, Nuffield, SGM, shipwrecks, Summer students

Monday, 10 September 2007

To coin a phrase.

MetaprotogenomoSIPolomics is where it's at. At least that's what I tried to convince the audience at the Edinburgh SGM meeting with my slightly rushed and results-lite presentation. I failed to record the talk, but will do a soundtrack myself so you can get an 'almost there' feel. Hopefully a Slideshare slidecast is all it's cracked up to be! When I get some time I'll mention some of the more interesting talks too, it was a good meeting, my buttocks have just recovered from sitting through it.

Posted by

Mike

at

14:56

![]()

Saturday, 1 September 2007

A quick note

Just getting packed for Edinburgh. The talk is at least set in my mind, the slides will change several times - it's not until Thursday and I keep thinking that I'll have all the evenings free. There are too many people to catch up with for that to be true!

Last week (or the one before) I stuck a note on my Facebook profile asking for help and suggestions writing the talk (mainly help avoiding bullet points - ick) and received 13 stunningly rude and innuendo laden replies. It's not me, it's my friends. It did serve as a reminder that there is, somewhat inevitably, a Facebook group for microbial ecologists, Microbial Ecologists United - linky (hope that works). Not as active as it could be, I always have intentions of posting job ads at least, lets see if I manage.

May update during the week if I find a nice wifi hotspot - otherwise, wish me luck!